Stephen Peach, assistant headteacher and business manager, Dacorum Education Support Centre, discusses how to prevent miscommunication

If you’re fortunate enough to be a parent, you’ll understand the joys and disappointments, the elation and frustration, the highs and lows, the time they need, the effort they require and the money they want. Oh, boy, do they need money.

Having children is the most difficult project anyone could ever undertake in life because you’ve got them always and forever and it doesn’t matter how much time, love, patience, money, gentleness, self-control, relationship-building, sympathy, resilience, reflection and money you put into them, you’re always left with the feeling that it’s never quite enough and that you could have done more. SBMs, I’ve observed, demonstrate similar feelings and attributes in the way they manage their tasks; larger projects can absorb as much time and resources as you care to give them and frequently leave you with the feeling that you could have done more.

Meanwhile, trying to look on the bright side, children will increase your levels of patience and perseverance, tolerance and negotiating skills immeasurably – though, it must be said, the one difference between bringing up children and a putting up a new building is that a building needs less intervention as it gets older…

In the building project I undertook a while ago I was fortunate in that, at a very early stage, we had a miscommunication issue between the five people who were co-ordinating the project. It wasn’t a big deal (no-one fell out!) but it was enough for me to realise that, as with everything in a school, the success of the project depended on organising the people to ensure they delivered what was wanted, at the time it was wanted.

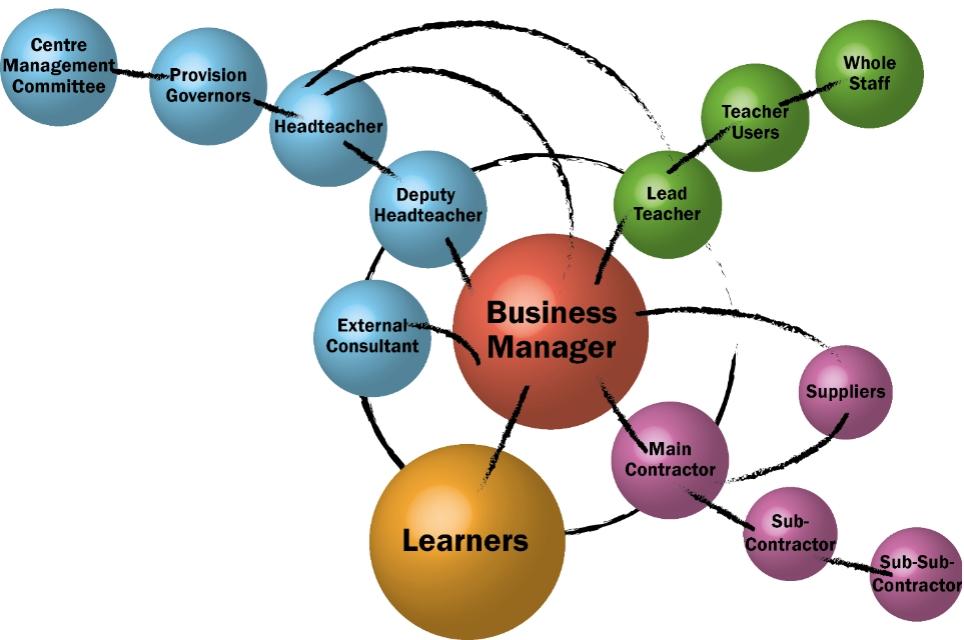

In my school the business manager is responsible for anything that isn’t directly classroom-related and I soon realised that everyone was coming to me to ask questions and request information. To ensure miscommunication didn’t happen again, I did two things.

Firstly, I needed to work out the status of everyone involved, what information they needed and what communication channels would be used for each one. Some people respond better to in-person discussions, while others prefer ‘phone calls and, still others, the speed of an email. I’ve tried to illustrate my thought processes like this…

These were all the people and groups of people who had an interest in the outcome that I had to deal with. By highlighting the spere of influence of each stakeholder, and where they fitted into the chain, I could work out why they needed the information, who it was for, and how often they wanted it.

Difficulties occasionally arose because people would try to shortcut established lines of communication, ending up with less than all the information they needed, so I soon worked out I needed to touch base with some people on a more regular basis to ensure everyone was working towards agreed goals, and not shooting off on a tangent.

It helped to work out who the disruptors were, as I was able to anticipate problems before they arose. These people were fully-invested in the project, and often came up with great new ideas and ways of working but, if these were out of step with what everyone else was working towards, progress needed to be re-negotiated quickly.

Secondly, I needed to ensure that each piece of information I received was delivered to everyone who needed it. In order to ensure no-one was left out I asked myself a series of questions along these lines:

- Who do I need to chase to get the information?

- Once it arrives, who needs to be thanked for providing it?

- Who needs to be aware of this information, but not act on it?

- Who needs to act on this information?

- Who needs to change what they are currently doing, as a result of this information?

- How does this information change what is scheduled to happen next?

You get the idea – there can be loads of different questions to fit in with the context in which you are working. Without being this specific, and taking time to work out all the destinations of each piece of information,you can see how misunderstandings and disagreements can quickly arise.

Equally, it helped me to analyse the behaviours of those people around me, to specify in my head what information they wanted, and how it needed to be presented in a way they could engage with and have confidence in.

Most of the time, it worked well! It’s time-consuming, and often tedious, but there were no more miscommunications for the duration of the project – in fact, working pro-actively in this way flagged-up problems earlier than would otherwise have been the case.

At the end of it all, my learning point from the whole experience was that there’s no such thing as too much communication during project management, and that things can quickly go wrong if there is any break in information flow.

Be the first to comment