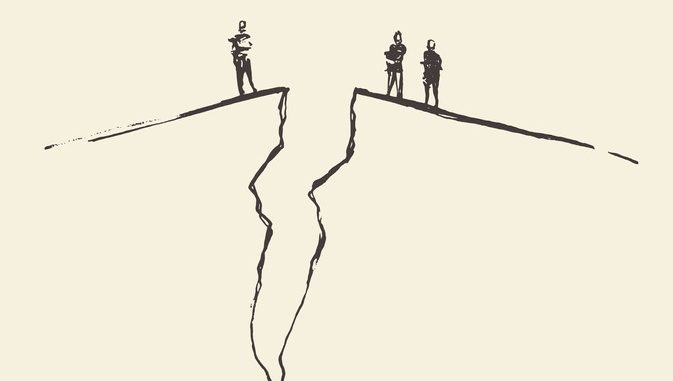

As reported by The Guardian, ministers have said more must be done to improve the attainment of disadvantaged pupils in England, after last summer’s exam results showed the gap between children from poor families and their better-off peers had widened further

A breakdown of GCSE results issued by the Department for Education (DfE) showed the gap between disadvantaged pupils and others increased for the second year in a row. The introduction of tougher exams appear to have halted the improvement seen in previous years.

“The attainment gap between disadvantaged children and their peers remains stable and is down by around 9% since 2011, but we recognise there is more to do,” said Nick Gibb, the school standards minister for England.

Just 456 of the 143,000 pupils classed as disadvantaged by the DfE achieved top grade 9s in English and maths last summer, compared with 6,132 out of 398,000 other pupils. The DfE classes about one in four state school pupils as disadvantaged, defined as having been eligible for free school meals within the five years before sitting GCSEs or if they have been in care or adopted from care.

While more than two-thirds of non-disadvantaged children achieved grade 4 or higher in maths and English, just 36% of those eligible for free school meals did so.

Of boys eligible for free school meals, those from mixed white and black Caribbean backgrounds had the weakest results, along with children from Gypsy or Roma families. Of girls eligible, those from a white British background also ranked lowest for attainment in English and maths among the main ethnic groups.

The Association of School and College Leaders criticised the government’s preferred progress measure, arguing that schools with a high number of disadvantaged pupils were likely to suffer. Schools are given a Progress 8 score – measuring the attainment of their pupils at GCSE against their levels when they left primary.

“Some groups of disadvantaged pupils make less progress than others because of challenges in their lives, and this can penalise schools with more disadvantaged pupils,” said Duncan Baldwin, deputy director of policy at the ASCL. Progress scores are also disproportionately skewed by a very small number of pupils with unusually low results which may be outside the school’s control, such as a pupil who misses exams because of a long-term absence. We would therefore urge extreme caution about ranking schools according to this data.”

The DfE also published national data on the performance of schools run by multi-academy trusts. This showed the Star Academies trust based in Blackburn made the fastest progress for its pupils for a second year in a row.

“It has always been our mission to improve the life chances of young people in disadvantaged areas by providing them with an excellent standard of education. Our results demonstrate that non-selective schools can compete with the very best in the country and make a real difference for our pupils,” said Hamid Patel, the trust’s chief executive.

But the overall figures suggested some multi-academy trusts were far less effective, with almost 40% reporting progress below the national average.

Meanwhile, a survey of the British public commissioned by the DfE found ‘an overwhelming consensus’ among UK adults on the importance of studying foreign languages, with 83% saying they should be studied at GCSE level and 61% agreeing that doing so would become more important in 10 years’ time.

Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, or connect with us on LinkedIn!

Be the first to comment